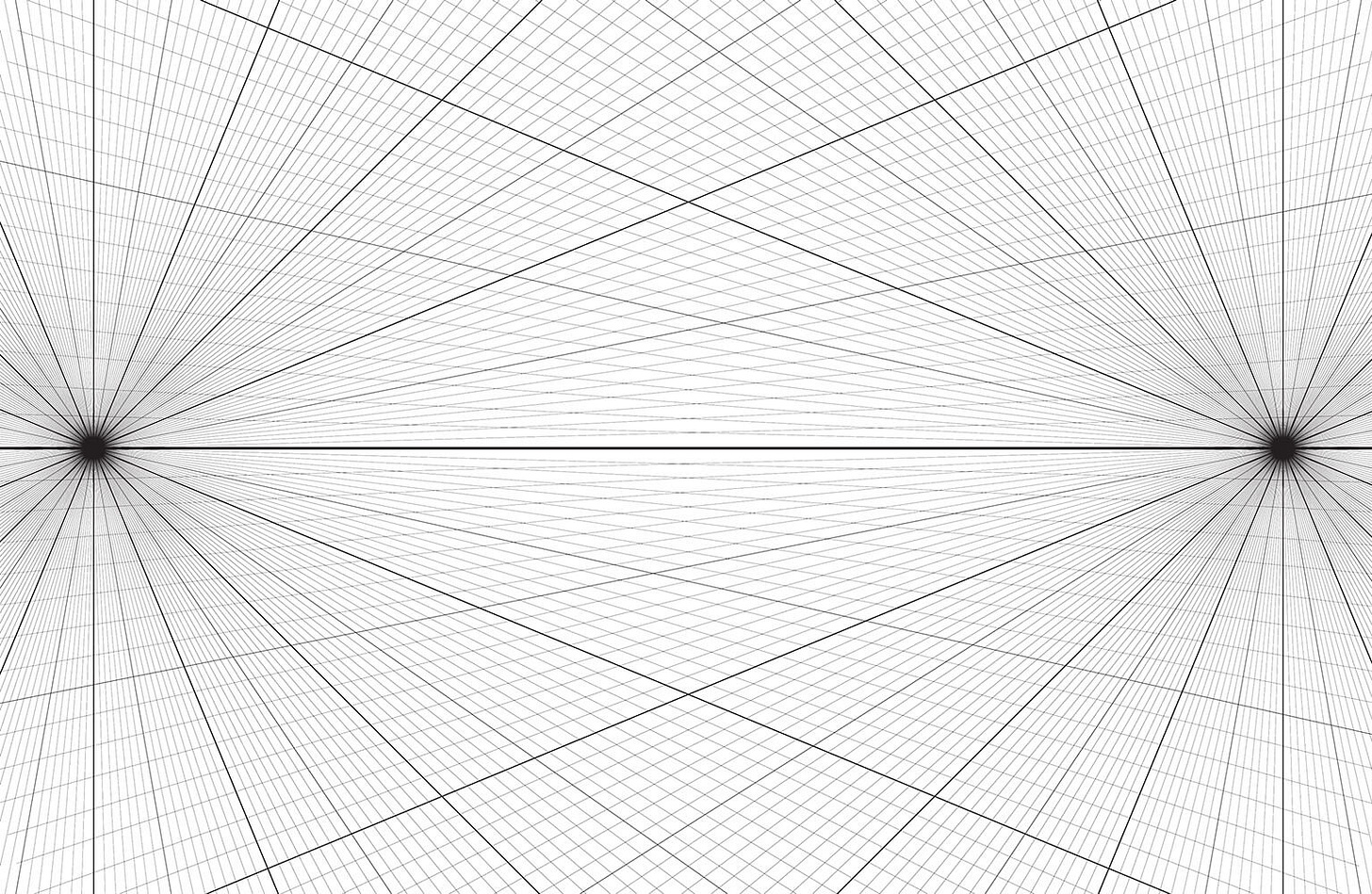

I’m looking at a beautiful landscape, registering its depths. I am looking into it. My eyes go first to the slate-blue mountains in the background laced with snow, the mists beyond that, then settle on the blazing clouds of twilight and the darkening mountain lake in the foreground. I compare the blues of the mountain peaks and the water, and contemplate the flecks of reflected light playing on the water’s surface before I see the one thing that really interests me: the horizon line made by the water, separating the mid-ground from the background. I compare that perfectly straight line with the entropy of all the other linear shapes around it, and it reminds me of something from art school: the idea that true "breadthless length" as Euclid described it, does not exist. Line is a convention of optics and mathematics. In other words, the horizon line is an illusion.

Straight lines, however, are important. Their instruction is paramount in the ways they help us to understand space and time. As design elements, their visuality is comforting in its correctness. We call them clean and necessary, and for many, they are beautiful. This is a bias of course, but I’m not thinking of either engineering or aesthetics, rather, the stabilizing symmetry of that line in the image, and the metaphorical horizon, another kind of fiction.

It’s the shining horizon of future plans and prospects, which I substantiate with a sense of stability that I pull out of a magician’s hat on a daily basis. It’s not that I live in a precarious situation, but I am very aware of how fragile life is. We spend our entire lives combating impermanence, and this is what I see when I gaze at that still lake bisected by that straight, yet false, line.

“Oh, but I have my fail-safes.”

Okay. Good for you, but …Life!

This trick of the mind, the calm line of stability where one might set a table and chair, may be the most important of all because believing it is the difference between a life of anxiety, doubt and inaction, and one of resilience and agency. We have a hope, and that sense of hope can die or escalate to a conviction: that stability can return to us after some catastrophic event in our lives has weakened us physically or spiritually. Resilience is what protects us from shame and varying degrees of self-harm, from sabotage to substance abuse or worse.

When we are boxed in or in some way trapped, unfortunate but not so uncommon, we are called upon to fight for our stability, even though most of the time we don’t really arrive at a flawless resolution. Not everything is a chess match to be won or lost. Resilience is all there is to fall back on sometimes, but what a mighty thing to have. It’s what redirects the spirit, which in turn convinces the mind to try again—and the mind does not budge without argumentation—to see the perfection in happenstance and to trust the mechanisms of faith.

How dangerous it is to take what we have for granted. All can be taken away, at any time. Eschewing gratitude is a sin, or should be, but the wounded ego will always interfere with this process, the gentle wisdom of forgetting and patience space for regeneration will not satisfy its deep need to redress wrongs, to control and compare and perform a host of other actions that serve itself better than the person.

As I was writing this, I came across this powerful quote from The Recognitions, where William Gaddis wrote:

“I know you, I know you. You're the only serious person in the room, aren't you, the only one who understands, and you can prove it by the fact that you've never finished a single thing in your life. You're the only well-educated person, because you never went to college, and you resent education, you resent social ease, you resent good manners, you resent success, you resent any kind of success, you resent God, you resent Christ, you resent thousand-dollar bills, you resent Christmas, by God, you resent happiness, you resent happiness itself, because none of that's real. What is real, then? Nothing's real to you that isn't part of your own past, real life, a swamp of failures, of social, sexual, financial, personal...spiritual failure. Real life. You poor bastard. You don't know what real life is, you've never been near it. All you have is a thousand intellectualized ideas about life. But life? Have you ever measured yourself against anything but your own lousy past? Have you ever faced anything outside yourself? Life! You poor bastard.”

Ecco, the ego’s mischief.

And where is the horizon line for a person who is close to suicide? I write all this today thinking about a friend of mine who’s in a bad way. Walking very close to an edge, that line, and wanting to fall off it.

When life comes crashing through the protective barriers and firewalls and fail-safe measures, the inexplicable and the unavoidable fly, moving like a freight train towards the inevitable. You, their friend, are there to see it: the crash happened, but miraculously, they didn’t die, and how to live after that is a thing to be determined. The post-suicide divides into a few categories. The ones who say, “Jesus, God, that was a close call! Thank you, Heavenly Father, that I couldn’t even get that right!”, the ones who say, “I was stupid…I should have…next time; I’ll keep that in mind...”, and maybe a third that say, “I will never have the balls to try that again.” Poor bastard indeed.

The main problem is that hope is gone. How do you restore hope to one who sees no horizon line at all? The future, exciting for some, might seem pure terror for others, pure potentiality without guarantees, an illusion. How to convince them otherwise, when in the present there is no stability, no dream, no hope? They will tell you they are tired of fighting, and this is the heartbreak.

If you know someone like this, I have to say: you can’t do a thing for this person. You might try and probably won’t be able to stop yourself. But if you get out on that ledge with them, you have to be aware that their jumping is not your fault. Let them know you’re there, sure, but they may kick you before leaping because “I’m here for you” is not necessarily what they want to hear. This does not give them the courage to take the next step. What does is the notion that they have no one. They will insult you in order to make that true. And then they will cast off into the non-space of their intention where you can’t follow them.

I have empathy, but I am not trained to handle my friend who is on the verge of ending their life, and what I see is that not even a trained professional is always successful in preventing suicide. To a certain extent, you have to prepare to let go of them. Pray that they don’t experience another paroxysm of loathing strong enough to trigger it. Yet they are my friend, and so no, I can’t accept it. I need them to live. Yes, to stepping back, but I can’t walk away.

I try to distinguish between what they say for effect and what they really mean. Happy when they answer me; still alive! I want to either become that horizon line—say the exact words that will make them come back in through that window—or help them find one, so they pull the boat towards it, and I want to believe they can find the resilience to continue living, but after all, it’s absolutely not about me. I can’t carry their pain for them.

I have to respect their decision.

It's none of my business, until they kind of make it my business. It's the information you now have, that you can't help feeling is a call to action. Yet, it's not.

I have read this twice, and will again. What an flavorful stew of philosophical and psychological conceptions. I know that feeling of hopelessness, or maybe I should say I knew it, well for worse or better, when the horizon seemed to be crushing my head as well as every other part of me, from the ages of 18-21. Only books, music, travel and nature could save me. (Viva Nuevo Mexico!) I’m debating the reality or unreality of the horizon line…maybe it’s real, and sometimes you’re up on the slopes with an amazing view, but other times you’re drowning. It seems to move around a lot.

About a year ago I realized that a person I loved unreasonably was suicidal. I made the mistake of thinking I could be of help in some way, not least because I spent so much time teetering on the same ledge. (But it’s always a different ledge, I think.) I’m not sure I was of any help whatsoever; she helped herself, apparently, though she did kick me on the way up. But she’s still alive.

(I wonder how much of it is a lack of hope, or an overwhelm of pain, or a brain chemistry out of whack, or maybe, too often, all three.)

Thank you for writing this.