I recently went to see an experimental piece of music by the late Maryanne Amacher1 called GLIA (2005), performed by Swiss music ensemble, Contrechamps, in collaboration with former members of Berlin-based Ensemble Zwischentöne (1988 – 2015). This performance was especially meaningful, as the composer had developed the piece with the German group for its premiere. Aside from the electronics, the instrumentation features two violins, two accordions, a cello, two transverse flutes, and piccolo in some sections.

I say music, but this work is not so much about music-making in the conventional sense, as a kind of sound shaping. Sound harnessing. It expresses time as forward moving sequences but there is no meter. There is no harmony or melody that one would identify as such. You might say, well, if it has neither meter nor harmony nor melody, then it’s noise. Yes and no. On that score, the hot water tap, in the bathroom of an apartment I used to live in, when opened, would make a beautiful metallic tone that was a perfect Bb.2 Our environment is full of sounds that conform to our sense of beauty if you think about it. Every hearing person has their favorite sounds, whether it be for what the sound is associated with, or because of its particular aural qualities: the sound of a hearty campfire, punctuated by small cracking sounds as the wood reacts to heat, the sound of rushing water with its negative ions, the whizz of a dragonfly, the cries of animals. We are comforted by the sounds of nature, and I daresay, all human beings born with the faculty have an internal catalogue of them.

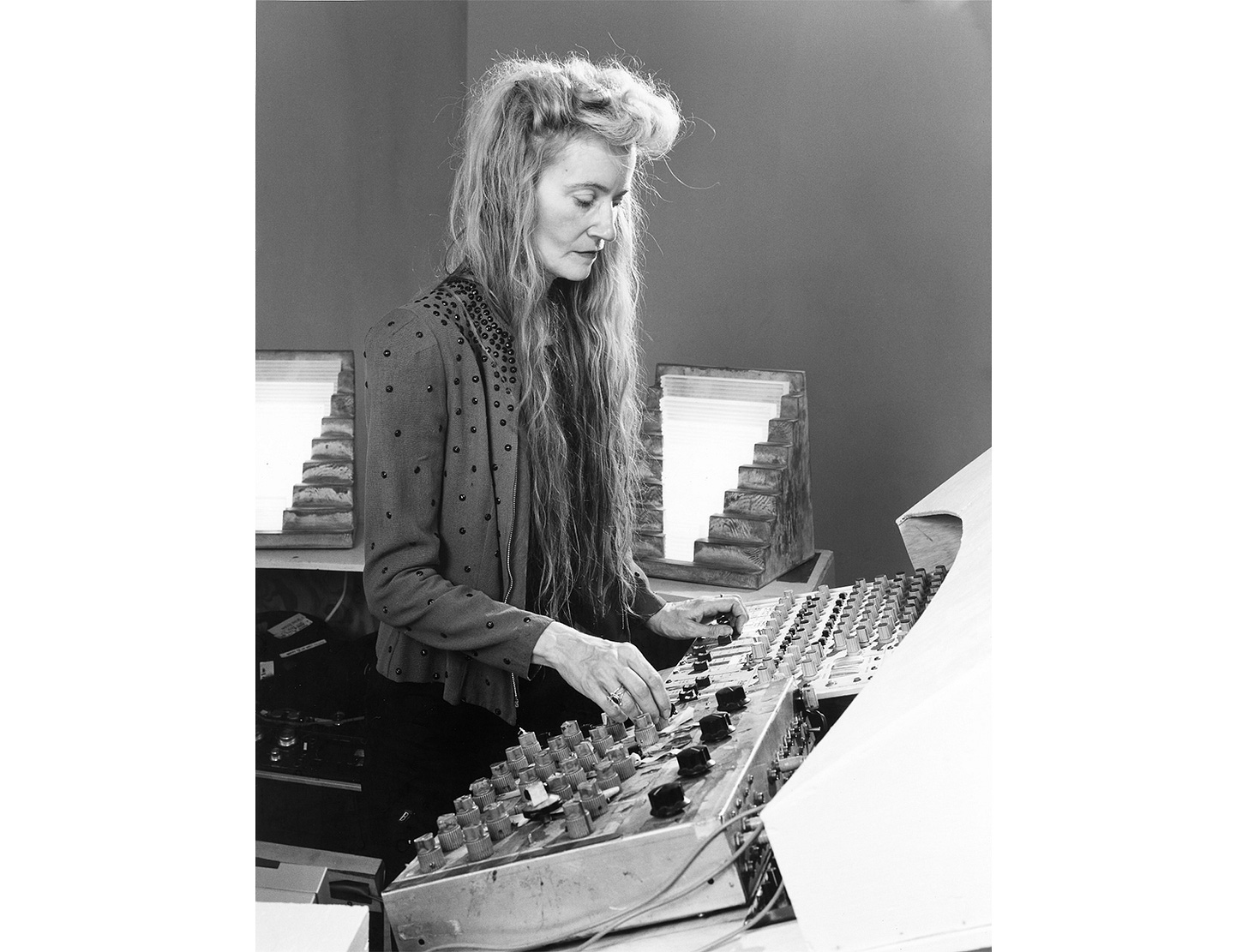

Then there are the industrial sounds we have all, most of us, grown used to. The sound of machinery, bells, buzzers and klaxons, the grating and grinding and screeching of metal. Sounds that infer great mass, or imply motion or explosions. A sensitive composer of this kind, an experimenter, is a listener to all the sounds of life, able to synthesize and gather a working vocabulary, a tool box, so to speak, of sounds that we can call organic and inorganic, and use them to express something human. This I believe is what Maryanne Amacher did.

There were a few extraordinary conditions in the performance of GLIA.

The Auditori of Carrer Lepant, Sala Alicia de Larrocha, in Barcelona, is small but optimal in the quality control musicians and sound engineers have. The space is equipped with moveable paneling that can change the acoustics. In this sense the room itself was one more instrument, but in fact all music uses space. David Byrne talked about this in his TedTalk of 2010, concerning how architecture helped music to evolve.

This was a standing concert, and most listeners stood or seated themselves on the parquet, but were invited to circulate throughout the concert space while the piece was in progress, as the musicians themselves did. There were passages which suggested that lying down would be the best way to appreciate the sounds, and many, including myself, did this as well. But Amacher’s soundworld lends itself more than anything to walking around, since many elements are multi-directional, and walking towards or away from them alters the listener’s experience in very specific ways. It is an art-music space that one inhabits.

So, what did it sound like?

On one level, it was like a single note sustained for seventy-five minutes. This is similar to the drone I spoke about last week, except that the character of the pitch never stopped changing. There was the inevitable confrontation or interaction—depending on the moment—between the analog and the digital, the electronic wave and the ensemble of classical or acoustic instrument. The electronic presence was proponderant, evoking, as I said before, both natural and industrial sounds. Some of it reminded me of the wildness and grandiosity of nature, and it is precisely in those moments that the acoustic instruments seemed to fight with and lose to, and rage against a fast-moving cloud of sound that rumbled inexorably across the room, and inundated the space like a force majeur. There were contrasts of power and vulnerability, and congruences between the two especially in the introduction and the finale.

As the deep rumbling ceased, there were whirring and buzzing sounds, and klaxon sounds loud enough to provoke a nosebleed.3 Chords were smears. Metallic clangs were accentuated by alternating high-pitched buzzer tones in a pulsing rhythm, topped with piccolo and flute. One could imagine avalanches or tsunamis or a patent ductus arteriosis4. The musicians played frenetically, as if only the greatest effort to counteract the sound that enveloped them could lead to a place of relative calm and the finale. In my mind, it’s sort of the opposite expressive direction to the story (probably apocryphal) of the string quartet that played on insouciantly, while the Titanic hit the iceberg, creating a dichotomy betweem creation and destruction, and the sounds of panic, and I would imagine, massive booms and creaking of the ship breaking up.

Of course these are my subjective imaginings. With a piece like this, it’s hard to keep the mind from making associations of this kind. I know that Amacher was largely unconcerned with what she placed in her soundscapes. Her fascination was with the perception of sound itself, ‘sound spatialization, and aural architecture’5. Rather than a musical experience, I would say GLIA creates an event that pitches the enhanced physicality of sound against the listener’s physiological reception of that sound, and the ideation it might provoke. A tremendously enriching experience it was. ◆︎

Born in 1938 in Kane, Pennsylvania. She enrolled in the University of Pennsylvania in 1955, where she studied with composer and theorist Constant Vauclain and composers George Rochberg and Karlheinz Stockhausen. Amacher went on to hold a series of fellowships – at the University of Illinois Experimental Music Studio (EMS), MIT’s Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS), SUNY Buffalo, Radcliffe, the Capp Street Project in San Francisco and many others, including international fellowships. After meeting John Cage at the University of Illinois in 1968, she went on to collaborate with him on Lecture on the Weather (1975) and later created Close Up (1979), the sound component for Cage’s Empty Words (1974). In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Amacher developed ‘Music for Sound-Joined Rooms’ and ‘Mini Sound Series’, presentational models for how her subsequent work should be ‘staged’. During the early 1980s, Amacher also worked on the materials for a multi-part drama originally imagined for TV and radio simulcast called Intelligent Life. While never fully realised, Intelligent Life reveals much of Amacher’s thinking on music and the advancement of potentialities for future listeners, transcending the social and physiological limitations of music as we know it. In the 1990s, Amacher continued to work internationally, and in the US she was commissioned to compose a large-scale work for the Kronos Quartet, received a Guggenheim Fellowship, performed at Woodstock 94, and released her first CD on Tzadik (Sound Characters, 1999). In the 2000s, she participated in the Whitney Biennial (2002), joined the faculty of the Milton Avery Graduate School of the Arts at Bard College, and released a second CD with Tzadik (Sound Characters vol. 2, 2008). In 2005 she received Ars Electronica Foundation’s Golden Nica, their highest honour. Amacher died in Kingston, NY after sustaining a head injury and a subsequent stroke during the summer of 2009.

I know it was B flat because I ran and got my traverse flute to find the pitch.

We were all given complimentary earplugs and told that we could leave whenever we needed to and come back in when we were ready to.

A kind of heart murmur

https://www.blankforms.org/the-maryanne-amacher-foundation